Musashi's first adoptive son, Mikinosuke

One of the few records to make any mention of Musashi's first adoptive son is the Bushū denraiki. It's author, Tanji Hōkin, claims Musashi met a young boy who was working as a horse handler at the Nishinomiya post station while he traveling along the Amagasaki highroad. A lively conversation ensues between the mounted warrior and the plucky young horse handler:

武州は馬上から、じっくりとかの少年の面魂を観察して、「おい、おまえ。おれが養子にして、よい主人へ出仕させてやろう。養子になれよ」と云った。しかし、少年が申すには、「仰せはありがたいことですが、老いた親があり、このように馬子をして養っています。あなたの養子になっては、両親が困ってしまいましょう。御免ください」と断わった。

Calling down from his horse, Musashi said “hey, you! How about me adopting you and placing you in the service of a good lord?” The station boy replied “I am very grateful for your offer, but I have aging parents and am supporting them by taking care of the horses. If I were to become your adoptive son my parents would surely fall on hard times, so please forgive me if I decline.”

Impressed by the boy's filial piety Musashi visits the boy's parents to persuade them to let him adopt their son, who goes by the name of Mikinosuke. The record then recounts how, “On his arrival there, Musashi told the parents of his intention to adopt their son and gave them some money so that they might support themselves for the time being. He also went and visited their neighbors, asking them to look after the parents.”

Though an entertaining and somewhat sentimental read, this version of events must at least be partly fictional, for we now know that Mikinosuke had already lost his natural father by the time he met his future adoptive father. That much is borne out by an ancestral record drawn up in 1696, and submitted to the administrators of the Okayama fiefdom in the province of Bizen by a certain Miyamoto Kohei, a nephew of Mikinosuke and head of a contingent of ashigaru of Ikeda Masakoto (1645–1700), the master of Okayama castle, on a stipend of two-hundred-and-fifty koku. Kōhei was fifty-five at the time, which means that, though he never knew Mikinosuke, he might have known Musashi’s other adoptive son, Iori, who must have visited the neighboring province of Harima regularly during the reconstruction of the Tomari shrine (see below).

Titled the Hōkōsho, Kohei's ancestral record claims that Mikinosuke was in fact the third son of Nakagawa Shimanosuke, a descendant of the lord of Nakagawabara castle in the province of Ise. Next to nothing is known about Lord Shimanosuke, except that, having served Sengoku Hidehisa (1552–1614) for a while in his early youth, he entered the service of Mizuno Katsunari, a close vassal of Tokugawa Ieyasu, and the man under whom Musashi served in the siege of Osaka castle (see Musashi's Battles). Like Musashi, Shimanosuke joined Katsunari in battle during the siege. He did so as a musha bugyō, or Magistrate of Warriors, and it is almost certain that he lost his life in the siege, for he disappears from the records in the wake of the battle.

Bearing this in mind, not all the of the above account may be fictional. The Nishinomiya station, after all, is only a few miles west from Osaka, the place that saw such heavy fighting during the winter and summer sieges of Osaka castle. Having lost his father in the summer siege of the castle, Mikinosuke might indeed have ended up working as a horse-handler in Nishinomiya. It is more likely, however, that Musashi had already met and befriended Mikinosuke's father before he fell in battle and took it upon him to look after his underaged son. Indeed, it might well have been Shimanosuke's dying wish that he do so.

Following the battle Musashi seems to have taken the boy to Hirafuku, where his beloved stepmother, Yoshiko, was still living with her new husband, Tasumi Masahisa (see Musashi's Mother). What is certain is that sometime after 1617 Mikinosuke entered the service of Honda Tadatoki (1596–1626). Tadatoki was the second son of Honda Tadamasa (1575–1631), whom Musashi had probably befriended during the siege. 1617 had been the year in which Tadamasa was promoted to the prestigious fief of Himeji. As the new master of Himeji castle, he had put his son in control of the Nitta han, another fiefdom in Harima of some ten thousand koku in size, although it had no castle and Tadatoki probably resided at Himeji castle.

In the spring of 1626, however, disaster struck when, wholly unexpectedly, Lord Tadatoki was taken ill with tuberculosis. By the middle of May Tadatoki’s health had deteriorated so much that he was unable to walk and forced to keep to his quarters in Himeji castle. For several more weeks he clung on to life, nursed by his devoted wife, the beautiful Senhime (who was the daughter of Tokugawa Hidetada), and his two pages, Mikinosuke and Iwahara Gyūnosuke. Tadatoki passed away on the last day of July. His remains were buried on the temple grounds of the Engyō temple in Himeji. They were interred with those of his only son, who had died in infancy only five years earlier.

Tadatoki was only thirty when he passed away, but in a society that put such store on loyalty to one’s lord and master Musashi knew the fate that now lay in store for Mikinosuke. The Bushū denraiki describes how:

武蔵は、そのころ大坂に居て、この事を聞き、「近日中に造酒之助が来るだろう。生涯の別れに、ご馳走してやろう」とのことである。かくて、しばらくして造酒之助がやって来た。武州は悦びに堪えず、盛大に饗応なさった。造酒之助は盃を所望して頂戴し、「これからすぐに姫路へ行くつもりです」と申し伝えた。「もっともの覚悟である」との武州の挨拶の言葉があった。造酒之助は姫路に至り、追腹したという。

Hearing of his lordship’s death, Musashi, who was then at Osaka, thought “Mikinosuke will presently come and visit me. We will have to part in this life. I’ll treat him to a feast.” And surely after some time Mikinosuke came. Musashi was beside himself with joy and treated his adoptive son to a banquet on a grand scale. Then, having toasted with his adoptive father, Mikinosuke said “after this I immediately intend to make my way to himeji castle.” Musashi saluted him with the words “it is becoming in you that you are thus prepared.” It is said that Kiminosuke then went to Himeji castle, where he followed his lord in death.

It was common practice in Mikinosuke’s days to immolate oneself on the death of one’s lord, a practiced called junshi. As tradition required, he did so in front of his master's grave on the sixth day following the latter's demise. He was only twenty-three years old. Had the incident happened half a century later, Kimonosuke would have been barred from following his master in death, for in 1663 the Edo Bakufu prohibited the practice by military decree. The Honda kakei, the private records of the Honda clan, captured Mikinosuke’s last moments, when it recorded his so-called jisei, or farewell poem:

おもわずも

雲井のよそに

隔たりし

ゑにしあればや

共に行く道

Though unexpected

separated now

by distant clouds,

Our bond would have it

that we take the road together

Miyamoto Mikinosuke’s grave can still be visited on the temple grounds of the Engyō temple. His grave is situated behind that of Honda Tadatoki and its inscription reads “Miyamoto Mikinosuke, Adoptive son of Miyamoto Musashi: Having served Tadatoki and committed seppuku in front of his master's grave, a native of Ise, and adoptive son of Musashi, aged twenty-three.” Immediately behind Mikinosuke’s grave is that of Mikinosuke's retainer, Miyata Kanbei. As Mikinosuke’s retainer, it was Kanbei’s role—and distinct privilege—to serve as his kaishaku, the person whose role it was to behead the one committing seppuku and thus relieve him from the terrible pain that accompanied this ritual. Left to Mikinosuke’s grave is that of Tadatoki’s only other page, Iwahara Gyūnosuke.

Musashi's second adoptive son, Iori

There are two important records that can be traced to Musashi's second son, Iori (the Kokura hibun being written on Iori's request by Akiyama Wanao (1618–73), abbot of the Taishō temple in Kumamoto). The two records in question were written following the reconstruction of the Tomari shrine. Situated near the village of Yoneda (present day Kakogawa city), the Tomari shrine was the family shrine of the Tawara clan. In Iori's time the shrine had fallen into disrepair, and it was somewhere during the early fifties that Iori and a number of locals undertook to restore the shrine. Work was completed in May 1653. To commemorate the occasion two munefudas, narrow strip of thin wood stating the construction's donors, builder, and date of completion, were attached to the inner beams of the shrine's upper structure. The Tomari jinja munefuda (1653) explain why Iori was so keen to preserve the shrine:

私の祖先は、六十二代・村上天皇の第七王子、具平親王より流伝して、赤松氏の出である。高祖刑部大夫持貞の代になると、時運がふるわなかった。故に、その顕氏を避けて、田原に改称し、播州印南郡河南庄米堕邑に住み、子孫代々ここに産まれた。

My ancestors are from the house of Akamatsu, descendants from Tomohira Shinnō, the seventh son of the sixty-second emperor Murakami. At the time of our distant ancestor Akamatsu Mochisada, an official at the Ministry of Justice, the clan fell on hard times. Being forced to shun the name of Akamatsu, they took on the name of Tawara and settled in the village of Yoneda, in the Kanan manor, in the district of Inami, in the province of Harima, where their children and their children's children were born.

Iori, then, was a scion of the Tawara of Harima. Family records of the Tawara clan furthermore reveal that he was born on 13 November 1612 as the second son of a certain Tawara Hisamitsu, a samurai in the service of Bessho Nagaharu (1558–80), the lord of Miki castle (also see Musashi's Mother). In 1578 Toyotomi Hideyoshi had laid siege to Miki castle, and having held out for a year and ten months, in January 1580, Nagaharu and his family agreed to commit seppuku on the condition that those who had served them would be spared. Reduced to the life of a rōnin, Tawara Hisamitsu took up farming near Yoneda, where he had two children, the second of whom was Iori.

According to the Bukōden, Hisamitsu had just passed away at the time Musashi met Iori. There had been two children, a son and a daughter, but the latter had been married off to a man from the village. The boy's mother had passed away earlier, so that the boy was living alone in a small hut, surviving on the little produce yielded by a wild plot of land in the shadow of the mountains. Though probably somewhat fictionalized, the Bukōden describes how, when passing through Iori's hometown on one of his musha shugyō, Musashi first spotted the boy catching loaches in a wet paddy field beside the road along which Musashi was traveling and that it was not much later that Musashi decided to adopt Iori.

Apart from mentioning that Musashi took pity on the boy the Bukōden does not dwell on Musashi's motives in adopting Iori—nor do any of the other extant records, for that matter. One of the reasons Musashi decided to do so, however, may well have been that, though not related, Iori was distantly connected to Musashi's stepmother, Yoshiko. She, after all, was the daughter of Bessho Shigeharu, master of Rikan castle, and a close relative of Hisamitsu's demised lord, Bessho Nagaharu (see Musashi's Mother). The Harima kagami's version of events is largely confirmed by the , a topography of Harima province compiled in 1762 by Hirano Yōsai. Like the Bukōden it states that Iori's father “was formerly a samurai at Miki castle of the Bessho clan, but following the fall of the castle, he moved to the village of Yoneda, where he sired Iori.”

The one true discrepancy between the two documents seems to be the place where Musashi met Iori, for the Bukōden claims it was near the village of Shōhōji in the northern province of Dewa (today's Akita prefecture, while the Harima kagami—in accordance with Iori's own writings—claims it was Yoneda. Masanaga’s claim, then, seems farfetched, but this is not necessarily the case. Old maps reveal that there used to be a village by the name of Shōhōji at that time, and that village was situated in the province of Harima. Significantly, no village by that name has ever been discovered on old maps of Dewa. The village in Harima has long since disappeared from Japanese maps, which is probably the reason why (in more recent times) it was assumed there must once have been a village by that name in Dewa. Shōhōji was situated some ten miles north of Akashi castle, in the Miki district of Harima province. In fact, it is still called Shōhōji, today, although it is now part of the Bessho district of Miki city.

Having adopted a second son, Musashi now felt responsible to secure the boy a safe future. Musashi, at this time, was residing at the nearby castle town of Akashi on the invitation of Ogasawara Tadazane (1596–1667), having been asked by the latter to design Akashi's new castle gardens. (Aware that the boy did not have warrior's blood running through his veins, he decided to secure the boy a different vocation. The Bushū denraiki mentions how, in the course of a conversation with Lord Tadazane, Musashi said: “by the way, I have a child in my care...He is no good for sword fighting, but he could serve you and may be of use when carrying errands to the council of elders and the like.”

Tadazane accepted Musashi's offer and took Iori into his service. This was in 1628. When, in 1632, Tadazane's was promoted to the Kokura fief in Kyushu, Iori moved down with him. It seems that Iori turned out to be a talented man, prudent, and endowed with a good sense of judgement. Having served a succession of Ogasawara notables, he eventually rose to the rank of chief retainer, with a fief of five thousand koku. According to the Bushū denraiki he enjoyed such a standing that even:

天下のご老中も、伊織をよくご存知になられ、世上でも名臣と噂するほどの者である。譜代の家臣たちは、敷居を隔てて坐し、道路を行くにも、伊織に塵がかかってはいけないと、二間ほど先を行かせ、残る面々は一列に後から行った。そんな具合でも、少しも、不遜とも奢るとも見えなかったそうな。

The elders of the realm [the Bakufu] were well acquainted with Iori, so much so that he was known even among the common man. The various generations of Ogasawara retainers would not be allowed to sit in the same room with him and when they accompanied him on the road they would keep a reverend distance of several yards for fear of soiling his attire with their splashing, thus forming a long row behind him. Yet in spite of this he did not display the slightest disrespect or pride.

Following the move to Kokura, according to the Harima kagami, Iori also “went out on the battlefield during the Shimabara rebellion, during which he rendered distinguished and meritorious service, and in reward for which his fief was increased in size to three thousand koku.” It seems that, though he may not have made a good swordsman, Iori was not wholly without military skills, albeit behind the battle lines. Iori passed away on 18 May 1678 at the age of sixty-six.

Miyamoto Iori's was originally buried beside the monument he had erected for his father in 1654, nine years after Musashi had passed away. The monument stands on the crest of Temukeyama, a small hill, some two hundred feet in height looking out over the island of Funashima on which Musashi once dueled with Sasaki Kojirō. Temukeyama lies on the outskirts of Akazaka, situated in the northern district of the port of Kokura, which at the time lay within Iori’s fief in the district of Kikunokōri.

In 1887, the area underwent a reconstruction to accommodate a battery guarding the Strait of Shimonoseki over which it looks. (The previous year the country had been shaken by the Nagasaki Incident, and tention betwen Japan and China was rising—a tention that was to result in the first Sino-Japanese War seven years later). The monument was transferred to the nearby Enmeijiyama (Akazaka), while Iori's grave was transferred to the southern foot of the Temukeyama. Since then Musashi’s monument has been returned to its rightful place, at the top of Temukeyama, but the graves of Iori and his descendants remains at the foot of the hill, close to the entrance of what is now called Temukeyama park.

Musashi's “third” adoptive son, Kurōtarō

If we are to believe the Hōkōsho (see above) Mikinosuke had a younger brother by the name of Kurōtarō. This Kurōtarō would later have two sons, the second of which was Kohei, the author of the Hōkōsho. The record, which is still held among the archives of the University of Okayama, claims Kurōtarō was living with Mikinosuke when the latter was in the service of Honda Tadatoki (1569–1626). This would suggest that Musashi might not only have adopted Mikinosuke after the siege of Osaka castle, but also his younger brother, Kurōtarō.

The Tōsakushi is the only other record to suggest Musashi might have had another son. Confusingly, it claims that the boy was called Shume and that he “was in the service of the Lord of Kokura, from the house of Ogasawara, and became a chief retainer with a fief of three thousand koku.” Obviously, its author, Masaki Teruo, who served Matsudaira Yasuchika, the daimyō of the Tsuyama fief in Mimasaka, is confusing things. It was, of course, Iori, who served Ogasawara Tadazane and moved to with him to Kyushu when the latter was promoted to the Kokura fief.

No other record makes any mention of Kurōtarō (or a boy called Shume, for that matter) in connection to Musashi. It is quite possible, therefore, that Mikinosuke took his younger brother under his care on his own account, after he had entered Honda Tadatoki’s service sometime after 1617 (the year in which Tadatoki was promoted to his new fief of Nitta in Harima).

Kurōtarō, according to the Hōkōsho, succeeded his brother after he had followed his master in death in 1626 at the age of twenty-three. Kohei claims that, following Tadatoki’s death, Kurōtarō accompanied his widow, Senhime, and their daughter, Katsuhime, on a visit to Edo with their stepfather Honda Tadamasa under the sankin kōtai system. Katsuhime later married Ikeda Mitsumasa (1609–82), which is how Kōhei came to enter the service of the Ikeda clan. As pointed out above, Kohei became the head of a contingent of ashigaru of Mitsumasa's son, Ikeda Masakoto (1645–1700) on a stipend of two-hundred-and-fifty koku.

Interestingly, while Kurōtarō is often referred to as Musashi's third adoptive son, technically, he would have been Musashi's second adoptive son, making Iori Musashi's third adoptive son. Kurōtarō, after all, had been orphaned along with his brother in 1615, when their father fell in the summer siege of Osaka castle. If Musashi indeed also took Kurōtarō under his wings following the siege, he would have done so several years before he adopted Iori.

Musashi's natural daughter

According to the Bushū denraiki Musashi had an affair in old age with a woman, who bore him a girl. It describes he was besotted with the child, but that at the age of three it suddenly fell ill and died:

武州は、悲嘆限りなく、朝から夕方まで小児の死骸を膝に置いて、嘆き暮らされた。さまざまに申し上げ慰めても、一向に聞き受けられない。武州には不似合な行いだと、隨仕の面々もいう...その後、死骸を葬ったのかとも問われなかった。生涯、その女児の話をされることはなかったという。

Musashi was inconsolable with grief and wept from dawn till dusk while he cradled the remains of the infant in his lap. People tried to console him but he did not hear them. Even his followers said that this was unbecoming in their master...I did not even hear whether he buried the remains, for throughout his life Musashi never again talked about the baby girl.

Remarkably, it's author, Tanji Hōkin, is one of the few to make any mention of Musashi’s relation with women and the only one to mention the birth of a child. There are, however, good reasons why Hōkin should be the only one to mention of this tragic episode. One reason, admittedly, is suggested by Hōkin himself, when he asserts that Musashi never again mentioned the deeply painful event to anyone. Apart from the fact that the child was born out of wedlock.

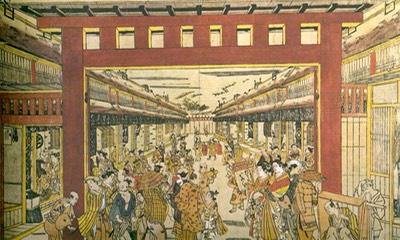

Another reason might be found in the kind of liaison that produced the child. Hōkin describes the woman as an omoimono, a word that can mean either a loved one or a prostitute, but there are strong reasons to suspect that the woman who was the object of Musashi’s affections belonged to the latter. And while it was quite normal in Musashi’s day for men to frequent the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters of Edo and the like, any child that was the product of such relationships was an embarrassment. It is only to Musashi’s credit that he deeply loved the child. Yet it is also understandable that if Musashi’s other early biographers were even aware of the liaison and its product they balked at committing it to paper. All of them, after all, were his desciples by descent and their chief aim was to extoll the virtues of the master, rather that expose his weaknesses, however human.

It is not surprising, then, that the only other source to make mention of such a liaison is Shoji Kasutomi, the sixth generation descendant of Shoji Jineimon, the founder of the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters in Edo. In his Dōbō goen, writes that “among the women of the establishment of Kawai Kenzaemon in Shinmachi there was a courtesan by the name of Kumoi who had a liaison with Miyamoto Musashi.” Writing his work in 1720, seven years before Hōkin was to complete his own, Jineimon cannot have had any knowledge of the Bushū denraiki, nor is it, given the geographical divide, likely that Hōkin had read the Dōbō goen. As long as no other sources are uncovered from the dust of time, we cannot be sure, either, whether Kumoi was the mother of the unfortunate child or whether she was one of Musashi’s other mistresses.

Any queries of remarks? Launch or join a discussion at our new FORUM